Having recently seen two of Clint Eastwood's most celebrated films—both directed by and starring him, both westerns, but a decade and a half apart—for the first time, I thought I might say a word or two about him as a filmmaker and about the films' places in the western genre.

Eastwood is best known for his westerns. (He's also known, of course, for his action/thriller films like the Dirty Harry series and his recent slew of excellent work behind the camera like Million Dollar Baby, Letters from Iwo Jima, and Changeling, but nothing in his career is as iconic as his westerns.) However, for most of his career the western was well past its peak in popularity. He came to fame in the mid-'60s with Leone's Man with No Name trilogy, but the genre was soon in decline, and Eastwood—along with others in the genre like Leone, Peckinpah, and Penn—had to adapt his westerns with the changing times and culture. Both The Outlaw Josey Wales and Unforgiven are classic examples of the "revisionist western," upsetting simple, long-held received wisdom in favor of a grimmer, more complex, and more "realistic" (obviously a problematic word) depiction.

— THERE GONNA BE SPOILERS AHEAD, I RECKON —

The Outlaw Josey Wales (trailer; I'm surprised Eastwood didn't sue the Army over that "army of one" slogan), released in 1976, starts giving us a different take on the western within the first five minutes, as Josey's wife and child are murdered by pro-Union guerrillas in Civil War Missouri, prompting him to join a rival pro-Confederate band that spends the war doing to Union sympathizers exactly what had been done to Josey. When all of his band but Josey surrender at war's end with the promise of amnesty, they're mowed down by the Union force accepting their surrender; the weapon used is what could be considered the symbol of revisionist westerns, the Gatling gun (also featured prominently in Django, Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, and Leone's Duck, You Sucker!). Josey's sidekick for most of the film is an old Cherokee, who recalls the Trail of Tears and rues ever trusting the white man. Unlike in classic westerns, Eastwood has us rooting for an outlaw and an Indian against a troop of U.S. cavalry; added to this are Josey's guerrillas' attacks on pro-Union civilians during the opening credits and the anti-war message at the end ("I guess we all died a little in that damn war."). As a film, I enjoyed it well enough, but I wasn't quite sure how it had gotten its "classic" status (including preservation in the National Film Registry). One thing that didn't quite sit right was the inconsistency in tone, back and forth somewhat clumsily between somber (the beginning, the massacre of Josey's crew, the Comancheros, the final fight and aftermath) and light (scenes involving the Cherokee sidekick and the pioneer grandma, Josey's tobacco spitting, the folks at the saloon). But, as I said, overall I enjoyed it.

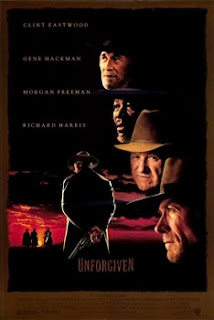

It's clear that Eastwood grew a lot as a filmmaker between 1976 and 1992, when he made Unforgiven (trailer). Its revisionism goes even deeper than The Outlaw Josey Wales's, questioning what's probably the fundamental element of the western genre, violence. Munny is a retired gunslinger with an exceptionally brutal past; though tamed for years by the love of his late wife, he takes one last job after some prostitutes put a price on the head of a john who cut up the face of one of them. Since settling down, Munny's tried his best to start a new, peaceful life, but events draw the monster back out of him. His adversary, Gene Hackman's Little Bill, is a particularly brutal sheriff, but his position—keeping hitmen from flooding his town—is more than understandable. There are no white or black hats here; everyone is some shade of gray.

Though there are some light elements like in The Outlaw Josey Wales, for instance Munny's difficulty in getting on his draft horse's back and the novelist who comes to town with English Bob, those are just a few brief glimpses of light through a generally somber tone. This is an Old West of indiscriminant killers, mutilated prostitutes, and dictatorial lawmen. The theme of dispelling the genre's illusions becomes express with the novelist, whose penny dreadfuls are the first wave of the romanticization of the West, further spreading the legends and lies already told by word of mouth about, for instance, Munny's and English Bob's gunslinging exploits, or the Schofield Kid's own exaggeration about killing the second hit mere seconds after the fact; as in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." While The Outlaw Josey Wales was good fun, Unforgiven is a real masterpiece; its violence is given gravity by the charm and humanity of characters like Morgan Freeman's Ned and the cut prostitute, and the pain and fear of the first hit as he bleeds to death in the dirt, whose only mistake was visiting a whorehouse with a short-tempered friend.

Eastwood's said that Unforgiven is his final western, and I can't think of a better one to end with, one that takes a hard, honest look at the genre and what it means. I think the western is America's national genre, for us what the samurai genre is for the Japanese (it's no coincidence that the two genres have informed each other for decades), and I'm very glad to see it reviving a bit in the last few years with such great examples as Brokeback Mountain, The Assassination of Jesse James, and No Country for Old Men, as well as TV series like Deadwood and Firefly. By giving the genre new stories to tell and new perspectives from which to tell them, the revisionism seen in Eastwood's westerns has only improved the genre and, hopefully, given it a new lease on artistic and entertainment life for generations to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment