A formerly cross-continental & cross-apartmental, now cross-town discussion on film featuring Owen and Matt

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Nice to see he kept busy after "American Beauty."

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Awesome

'ô-sem

adjective

Origin: awe, from the Old Norse agi, "fright," + the suffix -some, from the Old English suffix -sum, related to sama, "same."

1. extremely impressive or daunting; inspiring great admiration, apprehension, or fear.

2. extremely good; excellent.

3.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

The Clint Eastwood Western

Having recently seen two of Clint Eastwood's most celebrated films—both directed by and starring him, both westerns, but a decade and a half apart—for the first time, I thought I might say a word or two about him as a filmmaker and about the films' places in the western genre.

Eastwood is best known for his westerns. (He's also known, of course, for his action/thriller films like the Dirty Harry series and his recent slew of excellent work behind the camera like Million Dollar Baby, Letters from Iwo Jima, and Changeling, but nothing in his career is as iconic as his westerns.) However, for most of his career the western was well past its peak in popularity. He came to fame in the mid-'60s with Leone's Man with No Name trilogy, but the genre was soon in decline, and Eastwood—along with others in the genre like Leone, Peckinpah, and Penn—had to adapt his westerns with the changing times and culture. Both The Outlaw Josey Wales and Unforgiven are classic examples of the "revisionist western," upsetting simple, long-held received wisdom in favor of a grimmer, more complex, and more "realistic" (obviously a problematic word) depiction.

— THERE GONNA BE SPOILERS AHEAD, I RECKON —

The Outlaw Josey Wales (trailer; I'm surprised Eastwood didn't sue the Army over that "army of one" slogan), released in 1976, starts giving us a different take on the western within the first five minutes, as Josey's wife and child are murdered by pro-Union guerrillas in Civil War Missouri, prompting him to join a rival pro-Confederate band that spends the war doing to Union sympathizers exactly what had been done to Josey. When all of his band but Josey surrender at war's end with the promise of amnesty, they're mowed down by the Union force accepting their surrender; the weapon used is what could be considered the symbol of revisionist westerns, the Gatling gun (also featured prominently in Django, Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, and Leone's Duck, You Sucker!). Josey's sidekick for most of the film is an old Cherokee, who recalls the Trail of Tears and rues ever trusting the white man. Unlike in classic westerns, Eastwood has us rooting for an outlaw and an Indian against a troop of U.S. cavalry; added to this are Josey's guerrillas' attacks on pro-Union civilians during the opening credits and the anti-war message at the end ("I guess we all died a little in that damn war."). As a film, I enjoyed it well enough, but I wasn't quite sure how it had gotten its "classic" status (including preservation in the National Film Registry). One thing that didn't quite sit right was the inconsistency in tone, back and forth somewhat clumsily between somber (the beginning, the massacre of Josey's crew, the Comancheros, the final fight and aftermath) and light (scenes involving the Cherokee sidekick and the pioneer grandma, Josey's tobacco spitting, the folks at the saloon). But, as I said, overall I enjoyed it.

It's clear that Eastwood grew a lot as a filmmaker between 1976 and 1992, when he made Unforgiven (trailer). Its revisionism goes even deeper than The Outlaw Josey Wales's, questioning what's probably the fundamental element of the western genre, violence. Munny is a retired gunslinger with an exceptionally brutal past; though tamed for years by the love of his late wife, he takes one last job after some prostitutes put a price on the head of a john who cut up the face of one of them. Since settling down, Munny's tried his best to start a new, peaceful life, but events draw the monster back out of him. His adversary, Gene Hackman's Little Bill, is a particularly brutal sheriff, but his position—keeping hitmen from flooding his town—is more than understandable. There are no white or black hats here; everyone is some shade of gray.

Though there are some light elements like in The Outlaw Josey Wales, for instance Munny's difficulty in getting on his draft horse's back and the novelist who comes to town with English Bob, those are just a few brief glimpses of light through a generally somber tone. This is an Old West of indiscriminant killers, mutilated prostitutes, and dictatorial lawmen. The theme of dispelling the genre's illusions becomes express with the novelist, whose penny dreadfuls are the first wave of the romanticization of the West, further spreading the legends and lies already told by word of mouth about, for instance, Munny's and English Bob's gunslinging exploits, or the Schofield Kid's own exaggeration about killing the second hit mere seconds after the fact; as in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." While The Outlaw Josey Wales was good fun, Unforgiven is a real masterpiece; its violence is given gravity by the charm and humanity of characters like Morgan Freeman's Ned and the cut prostitute, and the pain and fear of the first hit as he bleeds to death in the dirt, whose only mistake was visiting a whorehouse with a short-tempered friend.

Eastwood's said that Unforgiven is his final western, and I can't think of a better one to end with, one that takes a hard, honest look at the genre and what it means. I think the western is America's national genre, for us what the samurai genre is for the Japanese (it's no coincidence that the two genres have informed each other for decades), and I'm very glad to see it reviving a bit in the last few years with such great examples as Brokeback Mountain, The Assassination of Jesse James, and No Country for Old Men, as well as TV series like Deadwood and Firefly. By giving the genre new stories to tell and new perspectives from which to tell them, the revisionism seen in Eastwood's westerns has only improved the genre and, hopefully, given it a new lease on artistic and entertainment life for generations to come.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Damn I wish we had HBO

So aside from currently airing The Pacific, a followup to the fantastic Band of Brothers, HBO is premiering next month a new show from David Simon, the creator of The Wire and it is called Treme. I am embedding the trailer below. It. Looks. Awesome.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

"What if I said you can have anything in the entire world?"

I just thought I'd catch up with the three most recent episodes, "Lighthouse," "Sundown," and "Dr. Linus," and share my thoughts, ideas, and questions. I thought all three were terrific episodes, very entertaining and enjoyable, though in different ways.

(As a very cool sidenote, the director of "Dr. Linus" was none other than Mario Van Peebles, of Heartbreak Ridge, New Jack City, Ali, and the biopic of his groundbreaking father Melvin, BAADASSSSS!)

"Lighthouse" and "Sundown" demonstrate what seem to be Jacob's and Loophole's respective M.O.'s in getting people to do what they want. In the former, Jacob (or his ghost, or whatever) has Hurley lead Jack out of the Temple to the previously unseen and unmentioned lighthouse, where he sees his childhood home in the mirrors; despite Jack's immediate reaction of anger and confusion, it leads him to believe in his importance to Jacob and to the Island's destiny, as seen in his later conversation with Richard inside the Black Rock. Jacob—much like Lost itself—often doesn't give people the whole truth but only what he thinks they need to know at the time, to the point of manipulating them, but ultimately leaves them to reach their own conclusions and make their own decisions. In "Sundown," on the other hand, Loophole promises people whatever they want to hear—that Sawyer will leave the Island, that Claire will get Aaron back, that Sayid will have Nadia, that Ben will rule the Island—and kills those who don't accept his devil's bargain. (Sure, he let Richard live, but perhaps he could tell that he'd try to kill himself within a few episodes anyway. Moreover, given that he killed at least a couple dozen Others at the Temple, the fact that he let one person live doesn't really change the equation that much.)

In "Lighthouse," Jacob told Hurley that he was sending him to the lighthouse—aside from getting him and Jack away from the Temple and letting Jack know he's his special little guy—in order to help someone find the Island. Then, at the end of "Dr. Linus," we see Charles Widmore (whom we haven't seen since last season) in a submarine offshore. Is he the one Jacob was talking about? My first instinct is no, that Jacob (who, while not perfect, seems better at least than Loophole) would never want Widmore (who sent Keamy's mercenaries in the fourth season and told Ben to kill Rousseau and Alex in the fifth) on the Island. But, on second thought, Widmore hasn't really been any more ruthless, devious, or "evil" than the rest of Jacob's followers; his beef seems primarily to be with Ben, who overthrew him and may not have been ruling the Others according to Jacob's wishes (their easy DHARMA-style living during his tenure contrasts with their simple ways before and since); and, most significantly, Widmore helped Locke to bring the Oceanic Six back to the Island, which, given their status as candidates, accords with Jacob's plans. At this point, despite my instinct to see Widmore as the "bad guy" (a dangerously simplistic concept on this show), I think that he's on Jacob's side; whether that'll end up being the "good" side, however, remains to be seen.

So Sayid has given in to the dark side. This is really tragic, given that his arc over the course of the series has been trying to overcome his past, his demons, and his fear that he's a "bad man" and undeserving of redemption or anything good in life. I read somewhere someone comparing him to an alcoholic who struggles for years to overcome his addiction, but finally gives in and embraces the bottle. Similarly, Claire has forsaken all else—friendship, morality, even sanity—in her quest to get Aaron back, turning into a latter-day Rousseau. Though Dogen said that Claire was "claimed" as Sayid was, how this happened remains unclear to me, since he apparently had to die first. Maybe she died in the mercenaries' assault on Dharmaville in the fourth season when a rocket blew up the house she was in, but she seemed fine when Sawyer found her seconds later; reader-of-the-dead Miles seemed weird around her after that, so it's possible that she died and returned to life claimed, but everything about her abandonment of Aaron and her appearance in Jacob's cabin with Christian still seems bizarre to me, so I hope we'll get some answers in that regard.

We've seen more evidence of the original timeline "informing" the new one. We haven't seen the cut on alterna-Jack's neck again, but we got some much clearer evidence in "Lighthouse" in his appendectomy scar; though his mother offers an explanation, the fact that he doesn't seem to recognize it indicates that it doesn't really belong in the new timeline, but is from the appendectomy Juliet gave him in the fourth season ("Something Nice Back Home"). And in "Dr. Linus," the fact that alterna-Ben teaches at Alex's high school, that he acts as her friend and mentor, and that he would sacrifice his own ambition for her sake, seems to show that the hard-learnt realizations of the original timeline—that power, and even the opportunity to do what he thinks is right, aren't worth sacrificing her—are nudging that Ben in a different direction, keeping him from repeating the original Ben's mistakes.

(Speaking of alterna-Alex, as much as I enjoyed Ben's flash-sideways, I had to suspend a lot of disbelief that she would be in LA, given that both her parents are French. I thought that, since her parents were scientists, maybe they held positions at universities in LA, but then I remembered that Alex said her mother had to work two jobs to pay the rent; I know academia can be rough, but not like that. I guess we'll just have to chalk it up to the Rule of Drama.)

I think that these episodes are three among the strongest in recent memory; in fact, these, in addition to "LA X" and "The Substitute," are giving me a lot of confidence about how the writers, directors, and actors will bring Lost to a close. In "Lighthouse," the two Jacks' parallel feelings of being in over their head and out of their element, their frustration and self-doubt, are finally overcome with a new-found sense of meaning, centeredness, and purpose. (Not only that, but it was pretty awesome seeing Jack as a father; it should be very interesting if we get to see more of David, given that daddy issues have defined Jack as a character. I do wonder, though, who his mother is; Jack met Sarah only a few years before taking Oceanic 815, but given how coincidence-prone the new timeline is, I wouldn't rule her out.) "Sundown" managed the rare feat of moving the plot forward briskly, delving into the mythology, giving us great character development and interactions, as well as awesome action and suspense, and having a tense and touching flash-sideways; it was the total package of Lost episodes. Though not much happened plot- or mythology-wise in "Dr. Linus," it was a powerhouse of character development and acting, thanks above all to Michael Emerson's complex and shattering performance. (Seriously, Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, just give him and Terry O'Quinn their Emmys now.) Ben's conversation with Ilana after he runs for the rifle ("Because he's the only one that'll have me.") was one of the half-dozen or so most moving scenes in the entire series, up there with Boone's death, Michael's killing Ana Lucia and Libby, the end of the third-season finale ("We have to go back!"), and Alex's death. "Dr. Linus" may be the best episode of the season thus far; I'd expect nothing less from Mr. Van Peebles.

P.S. — As much as I enjoyed "Dr. Linus," I was a little disappointed, at the end with all the happy reunions on the beach, everyone hugging and laughing in slow motion as the score swells, that we didn't see the reunited Ben and Richard slo-mo running across the beach into each other's arms, laughing and crying like a couple of girls. Would've been the perfect cap to a great episode. Oh well, can't have it all.

P.P.S. — Watching Ben and Alex's study session made me want to look up the Charter Act of 1813. That's how much of a history nerd I am. Turns out the answer was "the Punjab, Sindh, and Nepal."

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Just a girl

PRECIOUS:

BASED ON THE NOVEL "PUSH" BY SAPPHIRE. AN EDUCATION. Let me say first that I wrote this months ago when both of these movies were fresh on my mind but neglected to edit/link it up so it has sat there waiting. Until now. I've updated it slightly but glad that it comes from when both were fresh on my mind.

BASED ON THE NOVEL "PUSH" BY SAPPHIRE. AN EDUCATION. Let me say first that I wrote this months ago when both of these movies were fresh on my mind but neglected to edit/link it up so it has sat there waiting. Until now. I've updated it slightly but glad that it comes from when both were fresh on my mind.

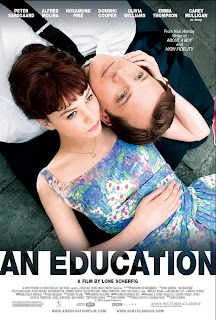

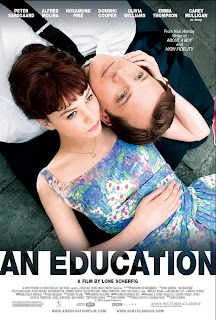

So both of these movies are about 16-year-old girls learning what it means to become a woman and evaluate their education. Both of these movies follow some of the general aspects of the coming-of-age movie -- the inspiring teacher, the lesson learned at the end, etc. It is quite odd that these two movies happen to come out in the same year at Sundance as they present two sides of the coin: Precious (trailer) is about a girl trying to escape being brought down in the slums of Harlem while An Education (trailer) follows a girl being yanked up into the good life of London and Paris a bit too early. I'm not quite sure how to connect the two films too much except in that they are, taken together, an example of how powerful the medium of film can be to transform what could be a standard story -- the archetypal coming-of-age -- into two completely different experiences. Other than that, I'll just have to write about the movies.

So I'll start with An Education, since that is the one you have not seen. I would say its worth catching sometime, if anything for the performance of Carey Mulligan in the lead role. My guess is she could become a bit of a big name in a few years as this movie shows some promising acting ability -- also she's quite pretty and that's always important in Hollywood. The role she plays is that of Jenny, a 16-year-old in 1961 with aspirations of attending Oxford and by doing so escape from the middle-class suburbia of her childhood. Although she is quite smart, she often drops French phrases, listens to greatest-hits albums, and gushes over art as if she is a lifelong appreciator. So when charming and fashionable David (a suave-looking Peter Sarsgaard) shows up and offers her a taste of the good life, she leaps right in even though she seems at least as clever as the audience and should realize something's not right. The screenplay (by novelist Nick Hornby based on Lynn Barber's memoir) delicately dances the line between her maturity and her childish musings without drawing a line between the two. If the first three-quarters are better than the ending, it still remains a well-crafted and fantastically acted movie. With some time to think on it, I kind of see it as not being particularly memorable except that years from now we might think of that movie as Mulligan's big debut to the big time. Plus she could pull an upset and outflank Sandra Bullock for the Oscar and make my night.

So I'll start with An Education, since that is the one you have not seen. I would say its worth catching sometime, if anything for the performance of Carey Mulligan in the lead role. My guess is she could become a bit of a big name in a few years as this movie shows some promising acting ability -- also she's quite pretty and that's always important in Hollywood. The role she plays is that of Jenny, a 16-year-old in 1961 with aspirations of attending Oxford and by doing so escape from the middle-class suburbia of her childhood. Although she is quite smart, she often drops French phrases, listens to greatest-hits albums, and gushes over art as if she is a lifelong appreciator. So when charming and fashionable David (a suave-looking Peter Sarsgaard) shows up and offers her a taste of the good life, she leaps right in even though she seems at least as clever as the audience and should realize something's not right. The screenplay (by novelist Nick Hornby based on Lynn Barber's memoir) delicately dances the line between her maturity and her childish musings without drawing a line between the two. If the first three-quarters are better than the ending, it still remains a well-crafted and fantastically acted movie. With some time to think on it, I kind of see it as not being particularly memorable except that years from now we might think of that movie as Mulligan's big debut to the big time. Plus she could pull an upset and outflank Sandra Bullock for the Oscar and make my night.

And then there's Precious. I was a bit nervous about this moving going in. Not because I was buying into the backlash (more later), but my concern was that the subject matter gaining it approval more so than the filmmaking. This also came from the choice of actors from the worlds of comedy and music that were getting such high praise -- I was worried it was being graded on a curve and I would end up disappointed. So I can say now that is not the case. Instead I must say this is truly a triumph for Lee Daniels in only his second movie as a director. There are a lot of ways that this movie could have gone wrong -- that it could have become the movie I feared (cough, Crash). But Daniels avoids nearly all of them to make a movie that is honest and realistic in its plot without sacrificing drama or emotion.

Never in the movie does it try to make Precious something that she is not. It could have been easy to make her extremely smart or artistic or possessing of some other skill that would allowed for an uplifting ending where she goes to college or makes it on a famous stage. The movie does not take this easy way out and presents Precious as no more than what she is: an obese, 16-year-old, pregnant, illiterate, black girl. What makes her the hero of this movie is not that she possesses anything special, but just that she is a human and no person -- even those without any other skills worth making a movie about -- deserves the poverty or abuse Precious suffers. Conversely the fact that she is poor, pregnant, the daughter of a "welfare queen," and black make her life no less interesting and worthy of having her story told. It just means that her life will never reach the levels Jenny glimpses, or even what she is trying desperately to escape. Some of my favorite parts of the movie are when we are reminded -- despite Precious' stony demeanor and adult challenges -- that she is just a girl. There are dream moments when she escapes from her situation by imaging herself at a photo shoot or film premier where Gabourney Sibide (a radiant actress who earned her Oscar nod and deserves a strong future) becomes a completely different person and we see a glimpse of who Precious could be. But the moment that stuck with me the most is a simple beat when she puts a hairband on her head, for just a little bit more femininity. It's a great, subtle moment and exemplifies for me how Daniels has much more faith in his audience than most filmmakers who delve into subjects of abuse or race.

Never in the movie does it try to make Precious something that she is not. It could have been easy to make her extremely smart or artistic or possessing of some other skill that would allowed for an uplifting ending where she goes to college or makes it on a famous stage. The movie does not take this easy way out and presents Precious as no more than what she is: an obese, 16-year-old, pregnant, illiterate, black girl. What makes her the hero of this movie is not that she possesses anything special, but just that she is a human and no person -- even those without any other skills worth making a movie about -- deserves the poverty or abuse Precious suffers. Conversely the fact that she is poor, pregnant, the daughter of a "welfare queen," and black make her life no less interesting and worthy of having her story told. It just means that her life will never reach the levels Jenny glimpses, or even what she is trying desperately to escape. Some of my favorite parts of the movie are when we are reminded -- despite Precious' stony demeanor and adult challenges -- that she is just a girl. There are dream moments when she escapes from her situation by imaging herself at a photo shoot or film premier where Gabourney Sibide (a radiant actress who earned her Oscar nod and deserves a strong future) becomes a completely different person and we see a glimpse of who Precious could be. But the moment that stuck with me the most is a simple beat when she puts a hairband on her head, for just a little bit more femininity. It's a great, subtle moment and exemplifies for me how Daniels has much more faith in his audience than most filmmakers who delve into subjects of abuse or race.

Where Daniels also succeeded is in the performances he brings out in his actors. Sure its possible that he pulled out award-worthy turns from women who had just been overlooked. But that would discount the ability of a talented director to help an actor bring out a quality performance. In an interview for a New York Times Magazine cover story on Precious, Daniels talks about working with Halle Berry in Monster's Ball, which he produced, and helping her dvelop that performance. I do not discount any of the actresses' work; I think Daniels just did a good job of finding and bringing out talent. The trailers do not give credit to the work of Sibide, whose Precious is much more nuanced than I was expecting. She certainly is able to portray the mask her character puts up and the emotion when it cracks, but also the more delicate task of keeping her a child and presenting the dream sequences as still the same person, but an idolized version of herself. Mariah Carey, otherwise known best in film for the bomb Glitter, turns in a wholly professional effort (from a role originally intended for Helen Mirren!) as a social worker that does not for one moment seem like a singer trying to act. Certainly the most surprising is Mo'Nique playing a mother incongruously named Mary. In her first scene she masterfully builds up into a furvor that makes a viewers jaw drop and continues this through most of the movie. Much has been written about how Carey appears without makeup, but Mo'Nique is scrubbed of any vanity and allows herself to be filmed looking like her character, not an actress. Although there are hints at more than just the mostrous aspects of her personality, her final scene takes one's breath away. Again it would have been easy to try and easilly redeem her or have her destroyed, but this movie does not take the easy way out and neither does Mo'Nique. At times she is lying and at times she is being honest. At times she is sympathetic and at times a monster. What's phenomenal about this scene is that the viewer -- and the characters -- are not sure where the distinctions lie and the ambiguity she maintains, even in an emotional scene, creates a single scene that could win her an Oscar.

Mo'Nique playing a mother incongruously named Mary. In her first scene she masterfully builds up into a furvor that makes a viewers jaw drop and continues this through most of the movie. Much has been written about how Carey appears without makeup, but Mo'Nique is scrubbed of any vanity and allows herself to be filmed looking like her character, not an actress. Although there are hints at more than just the mostrous aspects of her personality, her final scene takes one's breath away. Again it would have been easy to try and easilly redeem her or have her destroyed, but this movie does not take the easy way out and neither does Mo'Nique. At times she is lying and at times she is being honest. At times she is sympathetic and at times a monster. What's phenomenal about this scene is that the viewer -- and the characters -- are not sure where the distinctions lie and the ambiguity she maintains, even in an emotional scene, creates a single scene that could win her an Oscar.

The movie has been all but locked out of the Oscars, aside from Mo'Nique, because of a lot of criticism and backlash to which it has fallen victim. There are some who think the movie heavy-handed, and I could imagine that something with as difficult a subject matter could get that label, but it fails to acknowledge the subtlety with which Daniels tells his story. What I find less acceptance for is the complaint that it is racist or otherwise a bad movie for the black community. Courtland Milloy wrote in the Washington Post: "In Precious, [executive producers] Oprah and [Tyler] Perry have helped serve up a film of prurient interest that has about as much redeeming social value as a porn flick." Now that it a bit overboard. At the beginning of the movie, I was a bit uncomfortable with Mary and found myself worrying about the perpetuation of the generally false welfare-queen stereotype. There have been horrible parents of many races in many movies, however, and to say that stories about black people should avoid this area falsely assumes black people need some sort of protection and also defeats the whole purpose of the movie, which is to show that even in the worst of situation, a girl can survive. This movie should survive and not have to have a happy ending as some have suggested in order to make us all feel better. We have to learn to feel better despite how horrible life can be and that is the message Daniels is trying to give us.

As different as these movies are, I find my processing of both of them was made better by seeing both. It is not a qualitative comparison of the two, but a simple look at how different an experience can be and how powerful film can be in telling them. As I mentioned, from the long view they are a similar movie but when one gets closer -- even to a medium view -- it becomes apparent that there is so much difference and that the process of growing up can never be the same. The world is just too complicated.

BASED ON THE NOVEL "PUSH" BY SAPPHIRE. AN EDUCATION. Let me say first that I wrote this months ago when both of these movies were fresh on my mind but neglected to edit/link it up so it has sat there waiting. Until now. I've updated it slightly but glad that it comes from when both were fresh on my mind.

BASED ON THE NOVEL "PUSH" BY SAPPHIRE. AN EDUCATION. Let me say first that I wrote this months ago when both of these movies were fresh on my mind but neglected to edit/link it up so it has sat there waiting. Until now. I've updated it slightly but glad that it comes from when both were fresh on my mind.So both of these movies are about 16-year-old girls learning what it means to become a woman and evaluate their education. Both of these movies follow some of the general aspects of the coming-of-age movie -- the inspiring teacher, the lesson learned at the end, etc. It is quite odd that these two movies happen to come out in the same year at Sundance as they present two sides of the coin: Precious (trailer) is about a girl trying to escape being brought down in the slums of Harlem while An Education (trailer) follows a girl being yanked up into the good life of London and Paris a bit too early. I'm not quite sure how to connect the two films too much except in that they are, taken together, an example of how powerful the medium of film can be to transform what could be a standard story -- the archetypal coming-of-age -- into two completely different experiences. Other than that, I'll just have to write about the movies.

So I'll start with An Education, since that is the one you have not seen. I would say its worth catching sometime, if anything for the performance of Carey Mulligan in the lead role. My guess is she could become a bit of a big name in a few years as this movie shows some promising acting ability -- also she's quite pretty and that's always important in Hollywood. The role she plays is that of Jenny, a 16-year-old in 1961 with aspirations of attending Oxford and by doing so escape from the middle-class suburbia of her childhood. Although she is quite smart, she often drops French phrases, listens to greatest-hits albums, and gushes over art as if she is a lifelong appreciator. So when charming and fashionable David (a suave-looking Peter Sarsgaard) shows up and offers her a taste of the good life, she leaps right in even though she seems at least as clever as the audience and should realize something's not right. The screenplay (by novelist Nick Hornby based on Lynn Barber's memoir) delicately dances the line between her maturity and her childish musings without drawing a line between the two. If the first three-quarters are better than the ending, it still remains a well-crafted and fantastically acted movie. With some time to think on it, I kind of see it as not being particularly memorable except that years from now we might think of that movie as Mulligan's big debut to the big time. Plus she could pull an upset and outflank Sandra Bullock for the Oscar and make my night.

So I'll start with An Education, since that is the one you have not seen. I would say its worth catching sometime, if anything for the performance of Carey Mulligan in the lead role. My guess is she could become a bit of a big name in a few years as this movie shows some promising acting ability -- also she's quite pretty and that's always important in Hollywood. The role she plays is that of Jenny, a 16-year-old in 1961 with aspirations of attending Oxford and by doing so escape from the middle-class suburbia of her childhood. Although she is quite smart, she often drops French phrases, listens to greatest-hits albums, and gushes over art as if she is a lifelong appreciator. So when charming and fashionable David (a suave-looking Peter Sarsgaard) shows up and offers her a taste of the good life, she leaps right in even though she seems at least as clever as the audience and should realize something's not right. The screenplay (by novelist Nick Hornby based on Lynn Barber's memoir) delicately dances the line between her maturity and her childish musings without drawing a line between the two. If the first three-quarters are better than the ending, it still remains a well-crafted and fantastically acted movie. With some time to think on it, I kind of see it as not being particularly memorable except that years from now we might think of that movie as Mulligan's big debut to the big time. Plus she could pull an upset and outflank Sandra Bullock for the Oscar and make my night.And then there's Precious. I was a bit nervous about this moving going in. Not because I was buying into the backlash (more later), but my concern was that the subject matter gaining it approval more so than the filmmaking. This also came from the choice of actors from the worlds of comedy and music that were getting such high praise -- I was worried it was being graded on a curve and I would end up disappointed. So I can say now that is not the case. Instead I must say this is truly a triumph for Lee Daniels in only his second movie as a director. There are a lot of ways that this movie could have gone wrong -- that it could have become the movie I feared (cough, Crash). But Daniels avoids nearly all of them to make a movie that is honest and realistic in its plot without sacrificing drama or emotion.

Never in the movie does it try to make Precious something that she is not. It could have been easy to make her extremely smart or artistic or possessing of some other skill that would allowed for an uplifting ending where she goes to college or makes it on a famous stage. The movie does not take this easy way out and presents Precious as no more than what she is: an obese, 16-year-old, pregnant, illiterate, black girl. What makes her the hero of this movie is not that she possesses anything special, but just that she is a human and no person -- even those without any other skills worth making a movie about -- deserves the poverty or abuse Precious suffers. Conversely the fact that she is poor, pregnant, the daughter of a "welfare queen," and black make her life no less interesting and worthy of having her story told. It just means that her life will never reach the levels Jenny glimpses, or even what she is trying desperately to escape. Some of my favorite parts of the movie are when we are reminded -- despite Precious' stony demeanor and adult challenges -- that she is just a girl. There are dream moments when she escapes from her situation by imaging herself at a photo shoot or film premier where Gabourney Sibide (a radiant actress who earned her Oscar nod and deserves a strong future) becomes a completely different person and we see a glimpse of who Precious could be. But the moment that stuck with me the most is a simple beat when she puts a hairband on her head, for just a little bit more femininity. It's a great, subtle moment and exemplifies for me how Daniels has much more faith in his audience than most filmmakers who delve into subjects of abuse or race.

Never in the movie does it try to make Precious something that she is not. It could have been easy to make her extremely smart or artistic or possessing of some other skill that would allowed for an uplifting ending where she goes to college or makes it on a famous stage. The movie does not take this easy way out and presents Precious as no more than what she is: an obese, 16-year-old, pregnant, illiterate, black girl. What makes her the hero of this movie is not that she possesses anything special, but just that she is a human and no person -- even those without any other skills worth making a movie about -- deserves the poverty or abuse Precious suffers. Conversely the fact that she is poor, pregnant, the daughter of a "welfare queen," and black make her life no less interesting and worthy of having her story told. It just means that her life will never reach the levels Jenny glimpses, or even what she is trying desperately to escape. Some of my favorite parts of the movie are when we are reminded -- despite Precious' stony demeanor and adult challenges -- that she is just a girl. There are dream moments when she escapes from her situation by imaging herself at a photo shoot or film premier where Gabourney Sibide (a radiant actress who earned her Oscar nod and deserves a strong future) becomes a completely different person and we see a glimpse of who Precious could be. But the moment that stuck with me the most is a simple beat when she puts a hairband on her head, for just a little bit more femininity. It's a great, subtle moment and exemplifies for me how Daniels has much more faith in his audience than most filmmakers who delve into subjects of abuse or race.Where Daniels also succeeded is in the performances he brings out in his actors. Sure its possible that he pulled out award-worthy turns from women who had just been overlooked. But that would discount the ability of a talented director to help an actor bring out a quality performance. In an interview for a New York Times Magazine cover story on Precious, Daniels talks about working with Halle Berry in Monster's Ball, which he produced, and helping her dvelop that performance. I do not discount any of the actresses' work; I think Daniels just did a good job of finding and bringing out talent. The trailers do not give credit to the work of Sibide, whose Precious is much more nuanced than I was expecting. She certainly is able to portray the mask her character puts up and the emotion when it cracks, but also the more delicate task of keeping her a child and presenting the dream sequences as still the same person, but an idolized version of herself. Mariah Carey, otherwise known best in film for the bomb Glitter, turns in a wholly professional effort (from a role originally intended for Helen Mirren!) as a social worker that does not for one moment seem like a singer trying to act. Certainly the most surprising is

Mo'Nique playing a mother incongruously named Mary. In her first scene she masterfully builds up into a furvor that makes a viewers jaw drop and continues this through most of the movie. Much has been written about how Carey appears without makeup, but Mo'Nique is scrubbed of any vanity and allows herself to be filmed looking like her character, not an actress. Although there are hints at more than just the mostrous aspects of her personality, her final scene takes one's breath away. Again it would have been easy to try and easilly redeem her or have her destroyed, but this movie does not take the easy way out and neither does Mo'Nique. At times she is lying and at times she is being honest. At times she is sympathetic and at times a monster. What's phenomenal about this scene is that the viewer -- and the characters -- are not sure where the distinctions lie and the ambiguity she maintains, even in an emotional scene, creates a single scene that could win her an Oscar.

Mo'Nique playing a mother incongruously named Mary. In her first scene she masterfully builds up into a furvor that makes a viewers jaw drop and continues this through most of the movie. Much has been written about how Carey appears without makeup, but Mo'Nique is scrubbed of any vanity and allows herself to be filmed looking like her character, not an actress. Although there are hints at more than just the mostrous aspects of her personality, her final scene takes one's breath away. Again it would have been easy to try and easilly redeem her or have her destroyed, but this movie does not take the easy way out and neither does Mo'Nique. At times she is lying and at times she is being honest. At times she is sympathetic and at times a monster. What's phenomenal about this scene is that the viewer -- and the characters -- are not sure where the distinctions lie and the ambiguity she maintains, even in an emotional scene, creates a single scene that could win her an Oscar.The movie has been all but locked out of the Oscars, aside from Mo'Nique, because of a lot of criticism and backlash to which it has fallen victim. There are some who think the movie heavy-handed, and I could imagine that something with as difficult a subject matter could get that label, but it fails to acknowledge the subtlety with which Daniels tells his story. What I find less acceptance for is the complaint that it is racist or otherwise a bad movie for the black community. Courtland Milloy wrote in the Washington Post: "In Precious, [executive producers] Oprah and [Tyler] Perry have helped serve up a film of prurient interest that has about as much redeeming social value as a porn flick." Now that it a bit overboard. At the beginning of the movie, I was a bit uncomfortable with Mary and found myself worrying about the perpetuation of the generally false welfare-queen stereotype. There have been horrible parents of many races in many movies, however, and to say that stories about black people should avoid this area falsely assumes black people need some sort of protection and also defeats the whole purpose of the movie, which is to show that even in the worst of situation, a girl can survive. This movie should survive and not have to have a happy ending as some have suggested in order to make us all feel better. We have to learn to feel better despite how horrible life can be and that is the message Daniels is trying to give us.

As different as these movies are, I find my processing of both of them was made better by seeing both. It is not a qualitative comparison of the two, but a simple look at how different an experience can be and how powerful film can be in telling them. As I mentioned, from the long view they are a similar movie but when one gets closer -- even to a medium view -- it becomes apparent that there is so much difference and that the process of growing up can never be the same. The world is just too complicated.

Insert Palin-approved title here

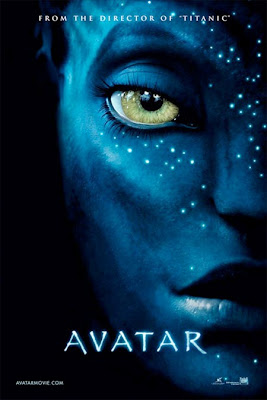

AVATAR. I feel like I should write something about the movie (trailer) because, aside from being the highest-grossing movie of all time, I think it will take home best picture at the Oscars tonight. It will make me almost as sad as the night the movie-which-shall-not-be-named won.

I feel like I should write something about the movie (trailer) because, aside from being the highest-grossing movie of all time, I think it will take home best picture at the Oscars tonight. It will make me almost as sad as the night the movie-which-shall-not-be-named won.

This is going to be much simpler because I agree with pretty much everything you already wrote. I do think that if it does when tonight, I will not be completely upset because as a technical piece of filmmaking, it has pushed the medium forward. James Cameron has created a 3D movie where, as you mention, it is not a gimmick intended to raise the price (making it easier to become the highest-grossing movie) but instead a full part of the experience. I found myself so immersed in what was happening that I eventually did not even notice the 3D and felt a bit more like I was a part of the action -- and shooting action has always been something Cameron has done well. Use of 3D was particularly useful for this story, which was about manufacturing a reality and someone becoming immersed in another world by proxy without becoming truly part of it. Something crosses over from being a gimmick to a stand-out approach when the form follows function, not the other way around. Being in 3D furthered his story and so he was right to use it here. I will be curious to see if he or any others are able to do the same when the plot is not quite so conducive to 3D.

So that is the good about Avatar. Now for the bad. I was so glad to see this movie got the general slap in the face of being nominated (and having a good shot at winning) best picture without so much as a nod for the screenplay, which does allow for 10 movies to be nominated. For all of the money spent on developing, shooting, and promoting this movie, you would think that Cameron and company could have invested in a screenwriter. He might be a talented director, but Cameron is tone deaf at writing dialogue. The story is somewhat ordinary but I was fine with the general arc of the movie. What I found inexcusable was how corny the dialogue was at times and the lack of any depth to the characters, other than possibly Jake Sully (Sam Worthington). Just as I think 3D is poorly used when it takes one out of the movie, a screenplay is bad when the ineptness of the language is so distracting that it takes the viewer out of the movie. I laughed and groaned at multiple times where it was not intended and entire scenes where ruined for me because I was so distracted by the bad dialogue.

In all Avatar is certainly a movie I would recommend seeing for its amazing visual effects that suggest what the future of film could be. It might have still been a movie I would say some might enjoy on DVD even without the benefit of the 3D movie experience, but Cameron went and ruined that opportunity. I am glad I went, but I cannot imagine sitting through that movie without the 3D and in that he has made sure that the movie for me is one that will not allow for repeat viewings.

This is going to be much simpler because I agree with pretty much everything you already wrote. I do think that if it does when tonight, I will not be completely upset because as a technical piece of filmmaking, it has pushed the medium forward. James Cameron has created a 3D movie where, as you mention, it is not a gimmick intended to raise the price (making it easier to become the highest-grossing movie) but instead a full part of the experience. I found myself so immersed in what was happening that I eventually did not even notice the 3D and felt a bit more like I was a part of the action -- and shooting action has always been something Cameron has done well. Use of 3D was particularly useful for this story, which was about manufacturing a reality and someone becoming immersed in another world by proxy without becoming truly part of it. Something crosses over from being a gimmick to a stand-out approach when the form follows function, not the other way around. Being in 3D furthered his story and so he was right to use it here. I will be curious to see if he or any others are able to do the same when the plot is not quite so conducive to 3D.

So that is the good about Avatar. Now for the bad. I was so glad to see this movie got the general slap in the face of being nominated (and having a good shot at winning) best picture without so much as a nod for the screenplay, which does allow for 10 movies to be nominated. For all of the money spent on developing, shooting, and promoting this movie, you would think that Cameron and company could have invested in a screenwriter. He might be a talented director, but Cameron is tone deaf at writing dialogue. The story is somewhat ordinary but I was fine with the general arc of the movie. What I found inexcusable was how corny the dialogue was at times and the lack of any depth to the characters, other than possibly Jake Sully (Sam Worthington). Just as I think 3D is poorly used when it takes one out of the movie, a screenplay is bad when the ineptness of the language is so distracting that it takes the viewer out of the movie. I laughed and groaned at multiple times where it was not intended and entire scenes where ruined for me because I was so distracted by the bad dialogue.

In all Avatar is certainly a movie I would recommend seeing for its amazing visual effects that suggest what the future of film could be. It might have still been a movie I would say some might enjoy on DVD even without the benefit of the 3D movie experience, but Cameron went and ruined that opportunity. I am glad I went, but I cannot imagine sitting through that movie without the 3D and in that he has made sure that the movie for me is one that will not allow for repeat viewings.

Saturday, March 6, 2010

War is hell, but it makes for good movies

THE HURT LOCKER. So in keeping with my attempt to catch myself up this will again be somewhat short. I ended up seeing the movie (trailer) on a whim as it was playing at the AFI theater, which is essentially one bus stop after the one I get off at and I decided just before pulling up outside the apartment complex to go on up and watch the movie.

THE HURT LOCKER. So in keeping with my attempt to catch myself up this will again be somewhat short. I ended up seeing the movie (trailer) on a whim as it was playing at the AFI theater, which is essentially one bus stop after the one I get off at and I decided just before pulling up outside the apartment complex to go on up and watch the movie.First off I should say I find movies that revolve around war appealing as the topic is pretty inherently dramatic. I also think the title of the movie is quite good with the idea of "hurt" being used not just to describe a creation of pain but also in common, especially military usage, to speak of using violence.

It is certainly an odd movie to peg and one that I think reminds me of our earlier discussion of the concept of genre and this is certainly a movie that leaves one questioning how it fits in. On one hand there is certainly an action-movie aspect to the film with a number of truly intense situations featuring the bad-ass character that like those Bruce Willis has made a career out of playing. In this case we get Jeremy Renner (a previously underrated actor) as Sergeant William James, a bomb technician in the Iraq war whose job is to defuse IEDs and takes a particular risky (and, as is the case in an action movie, effective) approach to his job. But the tropes of the genre break down quickly with the lack of a true dramatic event to allow our protagonist to shine and win the day. Instead director Kathryn Bigelow leaves us with the monotony of what James does and allows the viewer question the worth of his sense of duty and daring, an outcome rarely seen in an action movie.

I was reading a somewhat unrelated article on Slate this past week that referred to The Hurt Locker, stating that "despite its visceral view of war as madness and addiction, [it] has been pegged as an Iraq war movie that has nothing to say about the Iraq war: action cinema unencumbered by politics." It seems to me that it takes a bit of a turn there to which I do not completely concur with what the author states is the conventional wisdom. For the most part The Hurt Locker is a character study of a hardened man that one might have seen in a Scorcese-De Niro movie of the 1970s but dropped in the Iraq war. Furthermore to say it has nothing to say about the war is quite off base. There have been a number of movies made about the current conflict and none have done particularly well with audiences of critics (a topic I broached before) and this has been heralded as the first noteworthy film made about the war. The reason it has acheived this recognition is because it has avoided the heavy-handed morality most Iraq movies thus far have utilized. It is not a "political" film by any stretch of the imagination, but the blunt and realistic way it presents the danger and futility of the war says a lot about what this war is and allows the viewer to draw conclusions, a conclusion taken even further by a veteran in a NYT op-ed piece likening it and The Messenger to a public service. Bigelow does not tell me I should come out of the movie angry about how nothing was accomplished by anyone in the movie, but I still came out thinking it. It is not that the movie has nothing to say about Iraq; it is more accurate to say it does not tell me what I should think about Iraq.

Aside from that, from a technical standpoint it was also a pretty great experience. The atmosphere really felt like a war zone (albeit to someone who has never been in one) and not something that had been prettied up for the cameras. It was raw and not very pretty, much like I imagine this war to be. At times I found myself wondering how Bigelow accomplished this with so many extras -- including whaling women -- who appeared to be somewhat authentic locals as opposed to, say, Italians in costume. Bigelow has a good chance of becoming the first woman to win a best director Oscar and her masterful handling of those tense sequences that manage to be tightly edited yet keep the situation lasting more than just through the quick jump-cut sequences of a Jason Bourne movie. There is a sustained tension through her scenes. Again she is using her craft to say something about the Iraq war without having tell us what she is saying.

Aside from that, from a technical standpoint it was also a pretty great experience. The atmosphere really felt like a war zone (albeit to someone who has never been in one) and not something that had been prettied up for the cameras. It was raw and not very pretty, much like I imagine this war to be. At times I found myself wondering how Bigelow accomplished this with so many extras -- including whaling women -- who appeared to be somewhat authentic locals as opposed to, say, Italians in costume. Bigelow has a good chance of becoming the first woman to win a best director Oscar and her masterful handling of those tense sequences that manage to be tightly edited yet keep the situation lasting more than just through the quick jump-cut sequences of a Jason Bourne movie. There is a sustained tension through her scenes. Again she is using her craft to say something about the Iraq war without having tell us what she is saying.Overall I think it turned out to be a pretty spot-on movie and I would enjoy seeing her unseat her ex-husband from his place as the king of the world at this year's Oscars.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

The Life-cycle of the American Box Office (Cinematicus multimillionius)

The one I found most interesting is this chart by the New York Times showing the waxing and waning of weekly box-office receipts from January of 1986 to February of 2008; it also lets you select particular films to highlight how much money each made over what period of time. The crazy thing is, it looks almost like a living organism or other natural phenomenon, rhythmically expanding and contracting throughout the seasons. It confirms, in visual form, what we knew about the movie seasons: The big movies are released in the late spring/early summer and late fall/early winter, and there are noticeable lulls (in revenue and, usually, quality) January through April and again August through October. (There are examples, however, of break-out hits that create spikes in the midst of those seasonal valleys, like Liar Liar in March of 1997, The Matrix in March of 1999, Monsters, Inc. in October of 2001, The Passion of the Christ in February of 2004, and 300 in March of 2007.) In addition to the bulges being higher and sharper at the later end of the chart than at the earlier end, you can see how some films in the '80s were able to bring in a lot of money through a moderate but steady stream over a long time—Top Gun and "Crocodile" Dundee in 1986 are good examples of this—instead of the contemporary paradigm of a film's having to make most of its money during the first week or two of its release before dropping off precipitously. It's interesting to see the changes not only in how much money films made over the course of this period, but also in how they made that money.

Another cool chart depicts IMDb's Top 250 as a subway map, with genres as different lines and films that fit in multiple genres as transfer stations (for instance, Bonnie and Clyde lies at the intersection of Gangster and Romance, and King Kong sits atop World/Adventure, Thriller/Horror/Monster, and "Universally Acclaimed Masterpiece"). It really makes me want to watch (or re-watch) all of them by "riding the rails" along the various genres.

They've also got a chart depicting character interactions over the course of the story (the one for The Lord of the Rings is insanely convoluted for anyone but a Tolkien-nerd like me, while the one for 12 Angry Men is hilariously simple), one showing the time-traveling journeys of various characters (though nothing for the fifth season of Lost; you can find that here), and one giving a size comparison of several movie monsters, from tiny Chucky to the ginormous Cloverfield monster.

There you have it. Don't say I never did anything for you.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

The one with the gays, not the Jews

A  SINGLE MAN. To be fair, I gave the Coen brothers' movie its turn, so now for Tom Ford's picture to make sure I don't appear homophobic. Although only set 5 years apart, these two films could not be in two more different worlds and, as such, are approached in a completely different way. One of the remarkable aspects of movies is when a director can use the cinematic and aesthetic style of a movie to enrich their subject and although the brothers Coen certainly do this, albeit in a somewhat subtle manner -- No Country for Old Men exhibited a more firm grasp of this concept, using sparse filmmaking to tell a sparse story -- Ford truly nails it in his directorial debut.

SINGLE MAN. To be fair, I gave the Coen brothers' movie its turn, so now for Tom Ford's picture to make sure I don't appear homophobic. Although only set 5 years apart, these two films could not be in two more different worlds and, as such, are approached in a completely different way. One of the remarkable aspects of movies is when a director can use the cinematic and aesthetic style of a movie to enrich their subject and although the brothers Coen certainly do this, albeit in a somewhat subtle manner -- No Country for Old Men exhibited a more firm grasp of this concept, using sparse filmmaking to tell a sparse story -- Ford truly nails it in his directorial debut.

You again give a more than adequate synopsis in your earlier post, so for brevity's sake I will be lazy and just link to that for those who might want to know more of what the movie is about. I shall add, though, that I might not be a fashion expert, but I will have to play Bunk to your McNulty and say Ralph Lauren is not exactly the style of this movie -- something more clean and simple like Gucci or Prada or Dior. Watching the movie I found it to be a bit too polished at times with a house that looked impeccable and the wardrobe out of 1962's GQ. You could tell it was by a fashion designer and occasional magazine editor. But the more I thought about it the more I saw that this movie was truly being seen through the eyes of George Falconer (Colin Firth) who gets up every morning and creates a self that is not real and what we see is his interpretation of what is trying to create -- a world that is perfectly ordered and beautiful. The changing of the color saturation and the overall stylized cinematography further create this sense of unreality and polish that truly use the art of film as part of, not simply the medium for, an interpretation of Christopher Isherwood's novel. Plus as someone who also enjoys striking visuals in movies, I found the composition Ford and his director of photography, Eduard Grau, create to be quite the accomplishment from an artistic and technical standpoint.

I also cannot finish this without mentioning the work of Firth in this movie. If someone could win an Oscar for best performance in a scene, he would win hands down for the one in this movie when he receives a phone call (only partial clip) about his partner's death. So much of the acting that gets recognized is, well, the type of acting that gets ones attention, whether it be because the character is a well-known person or just happens to be particularly dramatic. George is neither of those and the true accomplishment of Firth's performance is how much raw emotion and complexity he brings to a character that holds so much in. We see the face George puts on every day and the times when the real him breaks through. The more I think about the movie the more I admire his performance and the more I think of how heartbreaking, with not too much dialogue on Firth's part, I found that scene on the phone to be. It is one of those moments in a movie that kind of takes your breath away.

Looking back on all that I have seen so far this year, I will have to agree with your assessment that A Single Man ranks near the top of the list.

Also in case one does not click through the links, this is the clip of the beginning of the telephone scene:

SINGLE MAN. To be fair, I gave the Coen brothers' movie its turn, so now for Tom Ford's picture to make sure I don't appear homophobic. Although only set 5 years apart, these two films could not be in two more different worlds and, as such, are approached in a completely different way. One of the remarkable aspects of movies is when a director can use the cinematic and aesthetic style of a movie to enrich their subject and although the brothers Coen certainly do this, albeit in a somewhat subtle manner -- No Country for Old Men exhibited a more firm grasp of this concept, using sparse filmmaking to tell a sparse story -- Ford truly nails it in his directorial debut.

SINGLE MAN. To be fair, I gave the Coen brothers' movie its turn, so now for Tom Ford's picture to make sure I don't appear homophobic. Although only set 5 years apart, these two films could not be in two more different worlds and, as such, are approached in a completely different way. One of the remarkable aspects of movies is when a director can use the cinematic and aesthetic style of a movie to enrich their subject and although the brothers Coen certainly do this, albeit in a somewhat subtle manner -- No Country for Old Men exhibited a more firm grasp of this concept, using sparse filmmaking to tell a sparse story -- Ford truly nails it in his directorial debut.You again give a more than adequate synopsis in your earlier post, so for brevity's sake I will be lazy and just link to that for those who might want to know more of what the movie is about. I shall add, though, that I might not be a fashion expert, but I will have to play Bunk to your McNulty and say Ralph Lauren is not exactly the style of this movie -- something more clean and simple like Gucci or Prada or Dior. Watching the movie I found it to be a bit too polished at times with a house that looked impeccable and the wardrobe out of 1962's GQ. You could tell it was by a fashion designer and occasional magazine editor. But the more I thought about it the more I saw that this movie was truly being seen through the eyes of George Falconer (Colin Firth) who gets up every morning and creates a self that is not real and what we see is his interpretation of what is trying to create -- a world that is perfectly ordered and beautiful. The changing of the color saturation and the overall stylized cinematography further create this sense of unreality and polish that truly use the art of film as part of, not simply the medium for, an interpretation of Christopher Isherwood's novel. Plus as someone who also enjoys striking visuals in movies, I found the composition Ford and his director of photography, Eduard Grau, create to be quite the accomplishment from an artistic and technical standpoint.

I also cannot finish this without mentioning the work of Firth in this movie. If someone could win an Oscar for best performance in a scene, he would win hands down for the one in this movie when he receives a phone call (only partial clip) about his partner's death. So much of the acting that gets recognized is, well, the type of acting that gets ones attention, whether it be because the character is a well-known person or just happens to be particularly dramatic. George is neither of those and the true accomplishment of Firth's performance is how much raw emotion and complexity he brings to a character that holds so much in. We see the face George puts on every day and the times when the real him breaks through. The more I think about the movie the more I admire his performance and the more I think of how heartbreaking, with not too much dialogue on Firth's part, I found that scene on the phone to be. It is one of those moments in a movie that kind of takes your breath away.

Looking back on all that I have seen so far this year, I will have to agree with your assessment that A Single Man ranks near the top of the list.

Also in case one does not click through the links, this is the clip of the beginning of the telephone scene:

The one with the Jews, not the gays

A SERIOUS MAN. I am not the only one to get these titles mixed up! When they first announced the Oscar nominations, I saw a couple of blogs accidentally mention that Tom Ford's movie (more to come on that) was nominated for best picture. Ha! Anyhow, I come roaring back into the movie commenting with this response to your post on the Coen brothers' most recent film and as the first step in catching up. I've got a lot of work to do so this will be one of many short posts on this year's movies.

A SERIOUS MAN. I am not the only one to get these titles mixed up! When they first announced the Oscar nominations, I saw a couple of blogs accidentally mention that Tom Ford's movie (more to come on that) was nominated for best picture. Ha! Anyhow, I come roaring back into the movie commenting with this response to your post on the Coen brothers' most recent film and as the first step in catching up. I've got a lot of work to do so this will be one of many short posts on this year's movies.It has been months since I saw this movie, so my memories are admittedly a bit more rusty than I would prefer. You wrote in your post (which you have conveniently already done months ago so I will link to that should a reader need at least a bit more plot synopsis) about perspective and while I think that is possibly one way to approach it, that was not as much what I took from the movie. It seems to me with the prologue and the main story, it was about the Jewish experience as a whole and the inevitability of the struggles the people face. No matter how much things seem to come together, you might enter a house and get stabbed. Or that test might come back positive. Or a tornado might be just off in the distance (the most literal example). For the Jewish people -- and the movie quite clearly makes the heritage of its characters the most defining part of their lives -- that danger is an inevitable outcome. But perhaps I have been watching too much Lost.

Seeing as how I'm trying to keep this short, I will say not too much other than that I think this movie fits in well with other movies in the Joel and Ethan's canon that finds humor in the mundane and, in many ways, the painful. This movie, as with many of theirs, never seem like heavy experiences yet delve into some of the gravest situations, be they murder followed by wood chipper or, in this case, more death, public shame, and the ending of a marriage. It feel right in the middle for me of their two most recent films, which present the more extreme of their serious and comic -- the latter being Burn After Reading, which I found to be a bit too overplayed and not nearly humorous enough to excuse it. If found this movie to be more genuinely funny and although it might not have been quite as much of an achievement as No Country for Old Men (and watching Unforgiven a few nights ago had me itching to rewatch No Country), but it was another example of the Coen brothers' ability to make a movie -- Fargo comes to mind -- that can have enough integrity for its subject matter and respect for its audience to include a seemingly unrelated prologue and a, shall we say, non-crowd-pleasing ending yet still make a movie that is highly entertaining. That ability to find humor where one would never think of finding it is one of their greatest gifts.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)