As the screen completed its slow fade to white, and the words "Directed by Darren Aronofsky" appeared to start the closing credits, I was breathless, my mouth agape, my eyes as big as saucers, my heart racing. The previous hundred ten minutes—and particularly the last twenty or so—had been one of the most thrilling, moving, transcendent experiences I'd ever had watching a film. After having seen thousands of films in my life, I found myself astounded anew at what this medium is capable of achieving.

(And I'm not just talking about Natalie Portman and Mila Kunis's "scene together." Though that was certainly memorable in its own right.)

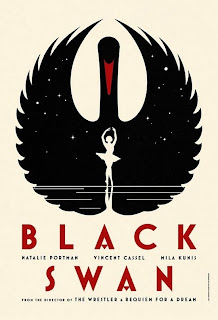

Black Swan (trailer) is the story of Nina (Portman), a talented ballerina in a New York ballet company, whose greatness is impaired by an almost childlike meekness and inexperience. However, the company's director, Thomas (Vincent Cassel), sees potential—and perhaps something else as well—in her, and chooses her for the lead in Swan Lake, requiring her to play both the pure, innocent heroine and her dark, seductive doppelgänger, the "black swan." The tremendous physical, mental, and artistic pressures that the role imposes as she prepares are compounded by the people around her: her encouraging but dominating and manipulative mother (Barbara Hershey), a ballerina herself before Nina's unexpected birth required her to give up her career; the retiring prima ballerina Beth (Winona Ryder), bitter over her seemingly premature sunset and the way the company—and Thomas in particular—used and then discarded her; and above all Lily (Kunis), a new arrival to the company whose uninhibited and passionate nature is exactly what Nina's "black swan" lacks, possibly both the key to getting Nina out of her artistic and personal shell and a ruthless rival trying to sabotage her big break. The strain of all this on the already fragile Nina takes a growing toll on her psyche, dragging her into paranoia, hallucination, and self-destruction.

Aronofsky's execution of this is fantastic. Portman's stunning performance is the best of her career. Her Nina begins seemingly in control, but only because never before seriously challenged; under her role's demands and Lily's influence, her brittleness becomes more and more apparent and threatens to shatter instead of strengthen her. (The role is funny because, like Nina, it is often said of Portman that, while very talented and attractive, she comes off as too sweet, delicate, and innocent to be really sexy, like a modern-day Audrey Hepburn. She's said that one reason she took the role was to try to shed some of that sweet-little-girl image and to be seen as more of a serious, adult actress.) Though pulling Nina in opposite directions, Kunis (whose performance won her the Mastroianni Award at Venice) and Hershey both nail the ambiguity their respective characters require, offering Nina comfort (in the latter's case) or liberation (in the former's) one minute and smilingly threatening her the next. Cassel has turned out to be one of my favorite actors this year, coming off his revelatory (to me, anyway) lead performance in the two-part crime-epic biopic Mesrine (trailer); here he not so much straddles the line between demanding mentor and exploitative scumbag as embraces both aspects of his character, accepting and exploring how they complement each other.

In addition to the cast, another aspect that stands out is the sound, and I don't just mean the Tchaikovsky. The incredibly demanding physicality of ballet is conveyed compellingly with the sounds of toes grinding on the floor like dull drills and clothes stretching and compressing as the dancers contort. Given that all this is usually drowned out by music during performances, actually hearing it during practice and rehearsals—no doubt accentuated for cinematic effect—gives an understanding of the great physical strain their bodies experience, while making visible and audible Nina's own psychological strain.

And speaking of physicality, Black Swan features enough cringe-inducing body horror to make Cronenberg proud. Not just the more fantastical transformations that Nina undergoes (of which the trailer offers a glimpse), but also the bodily damage resulting from the physical rigors of ballet and Nina's own increasingly high-strung nature: accidents from cutting finger- and toe-nails with scissors (which makes me uncomfortable regardless of the context), toe-nails breaking from pressure, nervous scratching and pulling at the skin around finger-nails. Though sometimes taken to gruesome extremes, this damage obviously results in far less harm or blood than your average horror film or thriller, but watching it did far more to ratchet up my tension, discomfort, and anxiety than most stabbings, gun shots, or beatings could. Though we never see much blood or gore, this film is not for the squeamish.

Regardless of its many art-house elements, Black Swan is, by genre, a thriller, like Aronofsky's debut, Pi; but it hews much more closely to the common themes and tropes of that genre, making it a more "thrillerish" thriller. The threats to Nina, even the ones only in her mind, are much more concrete than intellectual obsession; she comes to fear that people and forces are actually threatening her career and herself. This is where my only real criticisms of the film lie. (No, despite what all the praise above might suggest, I didn't think it was perfect.) Its faithfulness to familiar thriller tropes makes certain plot elements rather predictable: Of course the talented newcomer is going to be a rival and a threat to our heroine; of course the fading star whom she's replacing is going to be bitter and vindictive; of course the lights are going to go out and some blurred shape is going to rush past the end of the hall accompanied by a sudden, discordant crash on the score. I can't help but think the film could've forgone some of these "bump in the dark" moments and just let the tension come from Nina's more natural fears and disorientation; but this is a minor complaint for a film that does such a good job building a sense of threat, uncertainty, and loss of control. (Needless to say, it's handily unseated Argento's Suspiria (trailer) as the premier ballet-themed thriller featuring supernatural elements.)

Besides the film's artistic qualities, it also featured some core themes I found intriguing as well. One—probably the principal theme—is the idea of artistic creation through self-destruction. In order to play the "black swan" part of her role convincingly, Nina realizes that she must discard a good deal of who she is, the young, shy, inexperienced "white swan" who lives with her mother and has a bedroom full of stuffed animals. To achieve what the role demands, this butterfly must break out of her cocoon; but the process turns out to be a dangerous one, over which she has very incomplete control. She eventually begins to see positive results as her "black swan" performance improves, but what'll be left of her by the end as she lets go of her old life is uncertain. Before her stands the example—as both object of admiration and cautionary tale—of her predecessor as prima ballerina, Beth, whose great artistic highs went hand in hand with devastating personal lows. How far down Beth's road Nina will need to go is both a core element of the film's drama and a challenging question it poses about the creative process in general.

Another theme is that of the unreliable narrator. Though Nina doesn't literally narrate, we see the entire film through her eyes (I don't think there's a single scene without her), including her apparent hallucinations as her psyche breaks down. The subjectivity and unreliability of what we see is an obvious outcome of her psychological instability, but Aronofsky plays with this in interesting ways. For instance, Nina's hallucinations don't steadily become more dramatic and obvious; instead, obvious hallucinations are followed by events that seem plausible but on which doubt is later cast. ——— SPOILERS ——— For instance, obvious hallucinations like Nina's seeing her own face on a stranger, her mother's paintings screaming at her, and her growing wings during her "black swan" performance are interspersed with events like her sleeping with Lily, Beth's stabbing herself with her nail file, and Nina's killing Lily, which seem very real at the time but are later shown to be impossible or at least ambiguous. (Lily denies sleeping with Nina; Nina finds Beth's bloody nail file in her own hand after running away; and Lily turns up alive and well after Nina supposedly killed her.) ——— END SPOILERS ——— As a result, we begin to doubt (at least on first viewing) whether anything we're seeing, however plausible, is really happening or is merely in Nina's increasingly deranged mind.

Wow. There's so much more I could go on about: the captivating opening scene; Clint Mansell's haunting, operatic score; the grainy, heldheld-style photography (very like The Wrestler's) and its interesting contrast with the classical score and fantastical imagery; the camera's balletic movements around the actors. But I think I've written enough for now, to get my thoughts down while the experience is still fresh. Though not perfect—I'd have to rank it a little below The Fountain in Aronofsky's filmography, if only because a gorgeous time-skipping love story is a lot more pleasant to watch than Natalie Portman pulling at her cuticle until she tears it halfway down her finger—Black Swan is a gripping, intense, expertly crafted experience throughout, and in its conclusion rises to a beautiful, exhilirating euphoria rarely achieved by even the best. Perhaps it's just a matter of Aronofsky again shamelessly taking advantage of my well known weakness for pretty and emotive movies; even if so, he's done cinema a service in the process, and I couldn't be more grateful for it. You've triumphed again, Mr. Aronofsky.

P.S. — "I was perfect" is this year's "I think this just might be my masterpiece." Discuss amongst yourselves.